It’s not a sandwich, but an artistic and historical walking experience.

If you’re walking or driving around central Knoxville, you’ll see, on several corners, large traffic or utility boxes covered with fine art. “What’s the big idea,” you may ask. “Is downtown Knoxville some kind of art museum now?”

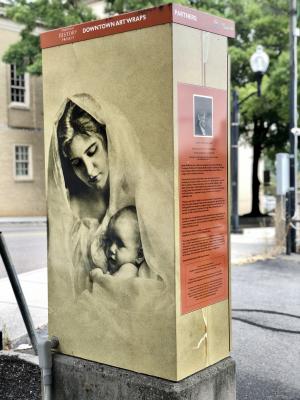

The short answer is yes, at least that’s our goal. Rather than leaving these gray aluminum boxes to attract vandalism and tagging, the Knoxville History Project proposes that they be beautiful, educational, and maybe inspiring, with our series Downtown Art Wraps. The idea is to use each of these utilitarian necessities as a canvas, of sorts, to display high-quality vinyl prints of notable local works of art, along with short biographies of the artists, sometimes with clues about the context of the art itself.

With the help of our partners, including the Knoxville Museum of Art, the Beck Cultural Exchange Center, Visit Knoxville, and the Arts and Culture Alliance, we’ve been quietly posting these works of art—with participation of the City of Knoxville—since 2017. They’ve proven durable—we do police them, and scrub off the inevitable splashes of spray-paint—and have engendered a good deal of discussion about local works of art. Some of them are famous, some undeservedly obscure.

In many cases, the art works are installed near a site relevant to the artist, and sometimes to the work itself.

|

|

|

| Mother & Child in Meadow, Catherine Wiley | The Toilers, Lloyd Branson | Knaffl Madonna, Joseph Knaffl |

Take the one at the corner of Gay Street and Union. The idyllic image of a woman and child in sunlight is one of many works by Tennessee’s best-known impressionist artist, Catherine Wiley. One of the earliest shows of her work was near here on Gay Street, during a street fair in 1897.

On the same block to the south, at Krutch Park, is a Smokies scene by Charles Christopher Krutch, once known as “the Corot of the South.” His early impressionistic landscapes of the Smokies inspired Knoxvillians before paved roads and the national park made the mountains accessible.

Further on, at the corner of Church Avenue, is a bright, striking view of men and horses pulling a heavy marble wagon up a hill. Called “The Toilers,” it’s probably the best-known work by Knoxville’s first full-time professional artist, Lloyd Branson. It’s here because it’s a high-profile spot to place a painting, but also because it’s half a block from the studio where Branson probably painted it around 120 years ago.

Down the hill at Church and State, visible from Gay, is our only artistic photograph so far, the once-famous Knaffl Madonna, by Joseph Knaffl, talented son of an Austrian immigrant. The image of sausage maker’s daughter Emma Fanz and Knaffl’s own daughter was shot on a Sunday afternoon in Knaffl’s studio on Gay Street in 1899, and became a bit of a national sensation, praised in magazines and duplicated nationwide. In recent years, it has adorned Hallmark Christmas cards.

Further along Gay Street at Cumberland, is a primitivist painting of Staub’s Opera House, by self-taught painter Russell Briscoe. It’s installed at the southeast corner at the location of its subject; the old Victorian theater was torn down in 1956. Briscoe was a downtown businessman who learned to paint when he was nearing retirement, but whose use of contrasting bright colors, usually to depict scenes of Knoxville history, impressed arts academics at the time.

One of those academics was UT’s Buck Ewing, a modernist who started the university’s art program. One of his own early paintings was that of a newspaper vendor, an eccentric old man who was well known on this sidewalk in the late 1940s. It’s on view at Gay and Main.

Down Main Street to the west is not a painting print but a photograph of a work of sculpture you’ll be pretty sure you’ve seen somewhere before. It’s one of the stone eagles high on the façade of the early 1930s federal building across the street. The sculptor, depicted with the statue on the art wrap, is Albert Milani, an Italian stonecutter who worked mostly in Knoxville from 1912 until his death in 1972.

|

|

|

| Red Tailed Hawk, Earl Henry | Lawson McGhee, John Kelley | Untitled Landscape, Beauford Delaney |

And nearby, half a block to the west, is a startling painting of a young red-tailed hawk, by Dr. Earl Henry (1911-1945). The artist, a dentist by trade, was serving in the U.S. Navy during World War II when his aircraft carrier, the U.S.S. Indianapolis, was struck by Japanese torpedoes and sunk in 1945, days before the end of the war. Dr. Henry was one of 300 sailors who died. This location connects to his legacy: before the war, Dr. Henry’s office was in the tall Medical Arts Building.

Not far from there, a couple of blocks to the west near Locust and Church, near the Lawson McGhee Library, is contemporary artist John Kelley’s portrait of the library’s honoree, daughter of library philanthropist Charles McClung McGhee; she who died in childbirth in 1883.

Within sight is a Smokies landscape by Rudolph Ingerle, the nationally known Vienna-born artist who came to the area early in the 20th century to try his hand at capturing the mountains, an inspiration for several notable artists. It’s near the YMCA, which coincidentally served as a home for several early Smokies conservationists.

Many of the paintings are by artists of mostly regional renown, but some have international reputations. Chief among them is abstract expressionist Beauford Delaney (1901-1979), who is as well known in the art centers of New York and Paris as in his hometown. He grew up in segregated Knoxville, recognized in school for his extraordinary talent, and accepted into the tutelage of Lloyd Branson, who helped him on his way to further study up north. First known as a colorful portrait painter, Delaney evolved in the 1950s into the abstract genre, and has been celebrated in his hometown mainly in recent years, with exhibitions, a national academic conference, and even a modern opera. His work is on display at the corner of Clinch and Henley—not far from the Knoxville Museum of Art, which has the world’s largest collection of Delaney’s work.

His very different brother Joseph Delaney, who almost coincidentally became a professional artist, too, specializing in urban streetscapes, is represented in other Art Wraps on the east side of town.

There are several others elsewhere in town, along Summit Hill, Jackson Avenue, Hall of Fame Drive, Magnolia, and elsewhere. The Knoxville History Project’s Art Wraps span more than a century of art and several different genres and eras, and we like to think they make a walk around downtown Knoxville even more interesting.

For a full guide to the Knoxville History Project’s Art Wraps series, including a map and gallery, see https://knoxvillehistoryproject.org/downtown-art-wraps/.