April is a historic month, especially regarding the Civil War. It was in April 1865 that the major armies of the Confederacy surrendered to U.S. forces, and that President Lincoln was assassinated. But it was also the month of the worst maritime disaster in U.S. history.

The steamboat Sultana exploded in the Mississippi River on April 27, 1865, killing an estimated 1,168 people, almost all its passengers the Union soldiers had recently freed from Confederate prisons. There are disagreements about how many died—some sources suggest it was hundreds more—and what caused the explosion.

What does that have to do with Knoxville? That dramatic tragedy happened 400 miles west of here.

As it happens, Knoxville has one of America’s largest monuments to America’s worst maritime disaster. It’s in Mount Olive Cemetery, just off Maryville Pike. It’s here because so many victims—and many survivors—of the explosion were Knoxville-area Union soldiers. The families of victims and about 50 survivors wanted to remember that event and got together to create a monument listing the names of all the known Tennesseans who were aboard that night, whether they lived or died.

South Knoxville is full of interesting landmarks, many of them tucked out of sight of major thoroughfares, but easy to get to, and pandemic-safe to visit.

Specifically, South Knoxville has far more than its share of authentic existing Civil War sites:

High Ground Park has been a low-key historical site, one that some Civil War enthusiasts don’t yet know about. It was originally Fort Higley, one of several Union forts that made Knoxville nearly impregnable during the last 18 months of the war. Interpreted by the Aslan Foundation, it makes for a beautiful walk through the woods, a 39-acre ramble along a bluff top, with one very surprising feature, the ruin of a “redoubt”—a small gun emplacement, barely big enough for a couple of cannons. It was almost forgotten for 150 years, on private property in semi-wilderness, known to only a few more intrepid historians. The charitable Aslan Foundation saved the property from proposed development and made it all much easier to access and understand, with interpretive signage and about a mile of easy paths.

Views of downtown and UT are better during the winter before the trees are leafy, so you’ll have a different experience if you visit soon. It’s located at 1000 Cherokee Trail.

Fort Dickerson, also recently improved by an Aslan project, was a better-known fort that actually played a role in the defense of Knoxville in November 1863, by firing some shots to discourage a Confederate advance guard. Because it’s within cannon range of downtown Knoxville, both sides knew that whoever controlled these heights could control the city. The Union guys got there first and held it effectively. Even though it was well known during the three-week Confederate siege of the city, Fort Dickerson was almost utterly forgotten for decades after the war. It was in the early 1930s that some kids exploring the thick woods on the hilltop wondered about these steep wall-like ridges and depressions. There followed a long effort to restore it, as Knoxville’s biggest surviving Civil War fort. There were once about 15 other Knoxville earthworks, once forbidding and effective, in the city that General Sherman called the best-fortified he’d ever seen, but they were developed away in the 75 years after the war. Only these hilltop fortifications, at the top of steep hills that were never tempting to developers of strip centers, remained. In 1963, Fort Dickerson drew hundreds of re-enactors and thousands of spectators for a centennial performance of the dramatic Battle of Fort Sanders—which couldn’t be held in its original location, because the neighbors, including the hospital, would complain. It was the biggest and noisiest battle re-enactment Knoxville has ever seen.

|

|

While you’re looking around, there’s a great deal to see in between, like the extraordinary Candoro Marble building, an Italian villa built of marble in the 1920s, but used as the office for a major marble company, recently a setting for neighborhood festivals; Little Switzerland, the startling modernist neighborhood designed by a German immigrant architect in the 1930s; the childhood home of America’s first African American federal judge and governor; Ijams Nature Center, whose combination of an Edwardian riverside bird sanctuary and several reclaimed marble quarries may be unique in the world; and the high-stylish grave of Paul Y. Anderson, a journalist who won the Pulitzer Prize for uncovering what was really going on during the Harding and Coolidge administrations. Plus Suttree Landing, the city’s newest public park—which, historically, began as a ca. 1880 waterfront horse-racing track.

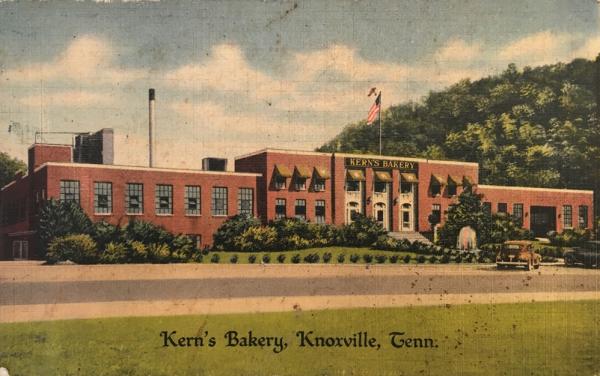

Even the streets of South Knoxville are historic: cutting South Knoxville right down the center is Chapman Highway, named for the Knoxville combat veteran and pharmacy executive who helped found the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The 1930s highway led to the nation’s most popular national park in the days when hundreds of thousands of Americans were driving their Packards and Model A Fords to see it for the first time. Finished about the same time the national park was, Chapman was a fun street, with souvenir shops, hot-dog stands and ice-cream parlors, drive-in restaurants, a bowling alley, and a high-school football field. You can still see a lot of that today if you know where to look. It can still be a fun street, too.

The Knoxville History Project recently released this free South Knoxville Driving Tour, all about things you can see from your car. Included is everything mentioned above—as well as what remains of the homes of John Sevier, Tennessee’s first governor—and Pulitzer-winning author Cormac McCarthy, who set some of his classic novels in South Knoxville.