How often do you think of Knoxville as the “Birthplace of Tennessee”? Whether you’ve heard that, or not, it’s one of our city’s distinctions. Many remember when a Gay Street plaque, now vanished, made that claim. It happened downtown, 225 years ago this winter. And it was no ordinary birth of a state, but an especially dramatic one, perhaps the boldest launch of a state in American history.

Involving several legendary pioneers, explorers and statesmen, a few Irish immigrants—and one future president—what happened would probably be historically notable even if they just got together for a Groundhog Day party. Of course, it was a good deal more than that. That winter, culminating on Feb. 6, 1796, 55 men from all parts of the territory, from here to the Mississippi River, came together in Knoxville, and after three weeks of argument and compromise, created a 41-page document. It was the first state constitution.

|

|

|

| Rowing Man Statue | Bijou Theatre |

Although some details of the event are murky, historians believe the three-week convention took place in the capacious office of U.S. Indian Agent David Henley. He was a government man, here mainly to keep the peace by making payments to the Cherokee. He wasn’t involved, but in a town that had no convention centers, auditoriums, or even church buildings, he was the only guy who had an office big enough to hold 55 guys and their aides. It was at the southwest corner of Gay and Church (today you’ll find a parking lot that faces the above popular “Rowing Man” sculpture to the north, the Bijou Theatre to the south, and various businesses to the east).

Frontiersmen generally didn’t like crowds. Hardly ever have so many famous frontiersmen gathered in one place. Some of them were already famous; some would become famous later.

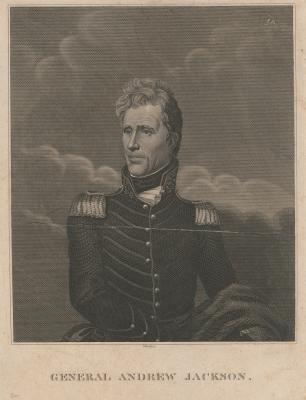

The 55 delegates to the constitutional convention, five elected from each of the 11 counties in the Southwestern Territory, included explorer-statesman James Robertson, founder of Nashville; James White, an original settler of Knoxville; Andrew Jackson, then a combative 28-year-old lawyer; William Cocke, a former member of the colonial Virginia House of Burgesses who would become one of Tennessee’s first senators; Archibald Roane, a Revolutionary soldier who had crossed the Delaware with General Washington, and who would become Tennessee’s second governor.

|

|

|

| Andrew Jackson – Courtesy Library of Congress | William Blount – Courtesy Blount Mansion | William Claiborne – Courtesy Wikipedia |

Perhaps the youngest member, only about 23—or by some sources, just 21—was attorney William Charles Cole Claiborne; he would later be the effective first English-speaking governor of Louisiana, for which he’s well-remembered in New Orleans, with the name of that city’s longest street, Claiborne Avenue. All told, among these 55 delegates, about a dozen were men who would have future Tennessee counties named for them. William Blount, territorial governor and signer of the U.S. Constitution, was the de-facto host, considering he lived just around the corner, and president of the convention.

Some were Revolutionary War heroes, some Irish immigrants. A remarkably large number of them were from Eastern Pennsylvania and had lived in Philadelphia. They were all white, of course. But it’s interesting that one of the distinctions of the first Tennessee constitution was that there was no racial qualification for voting citizenship. After 1796, free Black men—those not in the majority who were enslaved—could vote in Tennessee. (We should note it’s unclear how many actually did so—and that window closed 38 years later, when a second constitution drafted in Nashville reserved voting rights only for white men.)

In fact, as a whole, it’s not an embarrassing read. It presents concerns about mixing religion and politics and a perhaps surprising interest in global politics. These men meeting in Knoxville declared that the Mississippi River, 400 miles away, should never be controlled by a foreign power. When Spain and then France still controlled its mouth, that was a genuine anxiety.

|

|

Governor William Blount’s Office at Blount Mansion | courtesy Knoxville History Project |

Mainly they were interested in founding a state that could govern itself, not under the thumb of the President and Congress, as they had been previously. They didn’t have specific permission to do so, not from President Washington and not from his Congress. But they went ahead and elected a congressman and two senators—Jackson, Cocke, and Blount, all of them delegates at that Gay Street meeting. It was the constitutional equivalent of a Hail Mary pass.

It was precocious, arrogant maybe, but Congress couldn’t find anything legally wrong with it. Their Knoxville constitution was ratified in Philadelphia on June 1, now considered Statehood Day as of the 20th century. However, it’s clear from early writings that many of these early Tennesseans considered themselves a fully-fledged state on February 6, 1796. That specific date of the signing of the state constitution in Knoxville was celebrated in the state seal for about half a century.

Knoxville was capital of Tennessee for most of the period before 1819, when that status naturally gravitated to the state’s midsection. Sometime after that, the heroic era of the Knoxville constitution was forgotten. In the 1840s, the “Feb. 6” was quietly dropped from the state seal.

Reborn as a mainly industrial city, Knoxville plumb forgot about those dramatic days. But in the 1890s, when the state centennial stirred up some new interest in Tennessee’s earliest history, an old tavern at the corner of State and Cumberland began advertising itself as the “First Capitol of Tennessee.” Documentation was elusive, would-be historians didn’t have much to work with, and it’s largely a matter of speculation where the legislature met for the 20-odd years Knoxville was the state capital. But the old frame building on the corner known as Anthony’s Tavern made that claim that could not be easily disproven, forcing a place for itself as one of Knoxville’s first tourist attractions. It was torn down in 1929, after historians raised questions about whether the building was even there during the capital years.

|

|

Obelisk on Courthouse Lawn | Courtesy Knoxville History Project |

At the time of the state sesquicentennial in 1946 though, librarians and patriotic groups like the Daughters of the American Revolution worked together to assure that Knoxville’s role in the founding of Tennessee would never be forgotten. It was then that a comparison of ancient documents convinced historians that David Henley’s office, a building that had probably vanished before the Civil War, was the Birthplace of Tennessee. They installed a marble monument to that effect on the courthouse lawn and secured large bronze plaques on four buildings where significant events in the state’s founding happened. First among them was a “Birthplace of Tennessee” installed on the Victorian-era Knaffl Bros. building at the site of David Henley’s office.

|

|

Knaffl Building | courtesy McClung Historical Collection |

The problem with plaques is that they often don’t last any longer than the buildings they’re attached to. All four of the buildings that had Tennessee state historical plaques on them were torn down over the years. The last was the Knaffl building. The plaque on the Gay Street facade became less obvious when the building was given a fieldstone makeover—all the rage in the 60s—leaving a sunken square you could peer into to read the plaque. But the whole building was torn down after a 1995 fire, ironically, just weeks before the bicentennial of the signing.

That 1946 “Birthplace of Tennessee” plaque was saved, and the city has recently become interested in re-commemorating that spot, which is now a corner of the largest surface parking lot on Gay Street. But the plaque seems to have been misplaced in storage. Maybe it’ll turn up someday.

In the meantime, you can pay tribute to the bold gesture in several spots:

|

|

Blount Mansion | courtesy Knoxville History Project |

Blount Mansion, the home of the governor and convention president William Blount, was almost torn down for parking in 1925, but is the Knoxville region’s oldest house and the city’s only official U.S. Historic Landmark. You can visit the house, including Blount’s freestanding office, which is believed to be where the 1796 constitution was actually drafted. Blount Mansion will be celebrating the 225th anniversary of the Feb. 6 signing with a mini-documentary featuring Prof. Stewart Harris talking about constitutional aspects of the document and a furniture restorer talking about Blount’s desk, where the constitution was drafted—to be broadcast on Community TV, and also available on Blount Mansion’s website, as well as knoxvillehistoryproject.org.

There’s still one monument left from the 1946 sesquicentennial: the small white marble obelisk on the eastern part of the courthouse lawn, denoting Knoxville’s role as the state capital, is still there, though probably not seen as casually or often as it was when it was installed.

The First Presbyterian Church cemetery holds the graves of several people who had something to do with the constitution, including Governor Blount himself, and his wife, Mary, who probably served some hosting duties that winter; delegate James White; and Rev. Samuel Carrick, who was the convention’s formal chaplain.

The Museum of East Tennessee History, which is open with limited hours, includes the permanent narrative exhibit, Voices of the Land, which includes the general story and context of statehood in 1796; its location is on Gay Street, exactly one block north of the site of the signing. And, of course, you can stand on the very spot where it happened, though it’s now just the corner of a privately-owned parking lot.

The events of February 6, 1796 are remembered when statehood-minded activists in U.S. territories like Puerto Rico contemplate options to become a state. The action of drawing up a constitution, without waiting for congressional permission, is known as “the Tennessee Plan.”

The Knoxville History Project will devote its weekly Zoom event on Thursday, Feb. 4 at 6 pm, to the story of America’s most arrogant state constitution. For more on celebrating Tennessee’s Statehood, head here!